In batch operations, material is placed in a heavy metal ‘cage’ and a metal plunger is used to press the material. The main differences in batch press designs are as follows: a) the method used to move the plunger and apply the pressure; b) the amount of pressure in the press; and c) the size of the cage.

The plunger can be moved manually or by a motor. The motorised method is faster but more expensive.

Different designs use either a screw thread (spindle press) (Fig. 4, 5, 6) or a hydraulic system (hydraulic press) (Fig. 7, 8, 9) to move the plunger. Higher pressures may be attained using the hydraulic system but care should be taken to ensure that poisonous hydraulic fluid does not contact the oil or raw material. Hydraulic fluid can absorb moisture from the air and lose its effectiveness and the plungers wear out and need frequent replacement. Spindle press screw threads are made from hard steel and held by softer steel nuts so that the nuts wear out faster than the screw. These are easier and cheaper to replace than the screw.

The size of the cage varies from 5 kg to 30 kg with an average size of 15 kg. The pressure should be increased gradually to allow time for the oil to escape. If the depth of material is too great, oil will be trapped in the centre. To prevent this, heavy plates’ can be inserted into the raw material. The production rate of batch presses depends on the size of the cage and the time needed to fill, press and empty each batch.

Hydraulic presses are faster than spindle screw types and powered presses are faster than manual types. Some types of manual press require considerable effort to operate and do not alleviate drudgery.

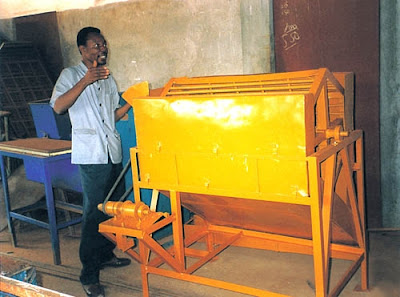

The early centrifuges and hydraulic presses have now given way to specially designed screw-presses similar to those used for other oilseeds. These consist of a cylindrical perforated cage through which runs a closely fitting screw. Digested fruit is continuously conveyed through the cage towards an outlet restricted by a cone, which creates the pressure to expel the oil through the cage perforations (drilled holes). Oil-bearing cells that are not ruptured in the digester will remain unopened if a hydraulic or centrifugal extraction system is employed. Screw presses, due to the turbulence and kneading action exerted on the fruit mass in the press cage, can effectively break open the unopened oil cells and release more oil. These presses act as an additional digester and are efficient in oil extraction.

Moderate metal wear occurs during the pressing operation, creating a source of iron contamination. The rate of wear depends on the type of press, method of pressing, nut-to-fibre ratio, etc. High pressing pressures are reported to have an adverse effect on the bleach ability and oxidative conservation of the extracted oil.

The main point of clarification is to separate the oil from its entrained impurities. The fluid coming out of the press is a mixture of palm oil, water, cell debris, fibrous material and ‘non-oily solids’. Because of the non-oily solids the mixture is very thick (viscous). Hot water is therefore added to the press output mixture to thin it. The dilution (addition of water) provides a barrier causing the heavy solids to fall to the bottom of the container while the lighter oil droplets flow through the watery mixture to the top when heat is applied to break the emulsion (oil suspended in water with the aid of gums and resins). Water is added in a ratio of 3:1.

The diluted mixture is passed through a screen to remove coarse fibre. The screened mixture is boiled from one or two hours and then allowed to settle by gravity in the large tank so that the palm oil, being lighter than water, will separate and rise to the top. The clear oil is decanted into a reception tank. This clarified oil still contains traces of water and dirt. To prevent increasing FFA through autocatalytic hydrolysis of the oil, the moisture content of the oil must be reduced to 0.15 to 0.25 percent. Re-heating the decanted oil in a cooking pot and carefully skimming off the dried oil from any engrained dirt removes any residual moisture. Continuous clarifiers consist of three compartments to treat the crude mixture, dry decanted oil and hold finished oil in an outer shell as a heat exchanger. (Fig. 10, 11, 12)

The wastewater from the clarifier is drained off into nearby sludge pits dug for the purpose. No further treatment of the sludge is undertaken in small mills. The accumulated sludge is often collected in buckets and used to kill weeds in the processing area.

In large-scale mills the purified and dried oil is transferred to a tank for storage prior to dispatch from the mill. Since the rate of oxidation of the oil increases with the temperature of storage the oil is normally maintained around 50°C, using hot water or low-pressure steam-heating coils, to prevent solidification and fractionation. Iron contamination from the storage tank may occur if the tank is not lined with a suitable protective coating.

Small-scale mills simply pack the dried oil in used petroleum oil drums or plastic drums and store the drums at ambient temperature.

The residue from the press consists of a mixture of fibre and palm nuts. The nuts are separated from the fibre by hand in the small-scale operations. The sorted fibre is covered and allowed to heat, using its own internal exothermic reactions, for about two or three days. The fibre is then pressed in spindle presses to recover a second grade (technical) oil that is used normally in soap-making. The nuts are usually dried and sold to other operators who process them into palm kernel oil. The sorting operation is usually reserved for the youth and elders in the village in a deliberate effort to help them earn some income.

Large-scale mills use the recovered fibre and nutshells to fire the steam boilers. The super-heated steam is then used to drive turbines to generate electricity for the mill. For this reason it makes economic sense to recover the fibre and to shell the palm nuts. In the large-scale kernel recovery process, the nuts contained in the press cake are separated from the fibre in a depericarper. They are then dried and cracked in centrifugal crackers to release the kernels (Fig. 13, 14, 15, 16). The kernels are normally separated from the shells using a combination of winnowing and hydrocyclones. The kernels are then dried in silos to a moisture content of about 7 percent before packing.

During the nut cracking process some of the kernels are broken. The rate of FFA increase is much faster in broken kernels than in whole kernels. Breakage of kernels should therefore be kept as low as possible, given other processing considerations.

No comments:

Post a Comment